By Sara Santiago

The return of The Forest School at YSE’s most foundational and traditional courses to both the field and the classroom was remarkable this fall. But the enthusiasm and passion of Thomas G Siccama Lecturer and Associate Research Scientist Marlyse Duguid ‘10 MF, ‘16 PhD, her teaching fellows, and students from across the university are what made these courses exceptional.

“It was such a relief to be able to take students in the field again. When we get to touch and see plants in their natural habitats it makes concepts so much more accessible,” says Duguid. “After being cooped up on zoom for the past year and a half, some outdoor class time is just what we needed. Plus, the weather was generally agreeable this fall, which doesn’t hurt.”

“Forest Dynamics,” a course that establishes the nuanced changes of forest structure and biodiversity over time for first year Master of Forestry (MF) and Master of Forest Science (MFS) students, attracted not only MF and MFS candidates but broadly YSE students, undergraduates, and students across various graduate schools at Yale, creating a remarkable class of nearly 40 students. In fact, the classroom location changed twice, landing in Bowers Auditorium in Sage Hall, in an attempt to accommodate the eagerness to study forests in the field.

Hannah Andrew ‘22 MF/JD, Genevieve Tarino ‘22 MF, and Eli Ward ‘18 MFS, doctoral candidate assisted Duguid as her teaching fellows, creating an all-female crew of forest dynamics instructors. As described by Tarino, student peer mentors – second year YSE students paired with first years to help acquaint them to the School – who took Duguid’s classes, highly recommended them to their mentees. Yale College undergraduate students who have completed internships under Duguid’s summer naturalist internships at Yale-Myers Forest also raved to their peers. According to Ward, who is also an instructor at the Yale-Myers MODs orientation course for all incoming YSE students, Duguid’s naturalist walks are always highly rated. All of this created a packed rollcall.

Duguid organized Forest Dynamics around various topics as well as field experiences, such as visiting local East Rock Park, as well as Sleeping Giant State Park outside of New Haven. Duguid also organized a trip to New York Botanical Gardens where Eliot Nagele ‘21 MF serves as the director for the Thain Family Forest and guided the class on a tour to discuss forest and invasive species management.

On a weekly and more intimate basis, students visited their own Place In The Woods (PITW), a Duguid cornerstone to learning forest dynamics right in the field. At the beginning of the semester, students chose an accessible place in the woods with a partner to visit weekly, spending an hour to witness and record observations. Ward explains that Duguid developed PITW last year when COVID-19 prevented field trips; students could still safely go into nearby woods to observes the processes of a dynamic forest. This practice carried through the semester and into the midterm exam as well.

At his PITW on the eastern shore of Lake Saltonstall on Regional Water Authority land, Bryce Powell water colored the exchange of forest nutrients and energy that come with autumn senescence, exhibited by leaf decomposition of various species at various stages and lingering Virgina creeper berries. Art by Bryce Powell ‘22 MEM, October 30, 2021.

At his PITW on the eastern shore of Lake Saltonstall on Regional Water Authority land, Bryce Powell water colored the exchange of forest nutrients and energy that come with autumn senescence, exhibited by leaf decomposition of various species at various stages and lingering Virgina creeper berries. Art by Bryce Powell ‘22 MEM, October 30, 2021.

This practice connects forest-focused students with a specific place and to the course material while promoting an understanding of the changing dynamics in the woods from summer to fall. Students journaled their ecological observations at various scales, from the forest floor to the canopy, capturing glimpses of what they could in their hand-drawn maps, illustrations, photos, and words. For students also studying in Duguid’s Dendrology course and Professor Craig Brodersen’s Plant Ecophysiology course, they had the opportunity to apply learnings from those disciplines as well.

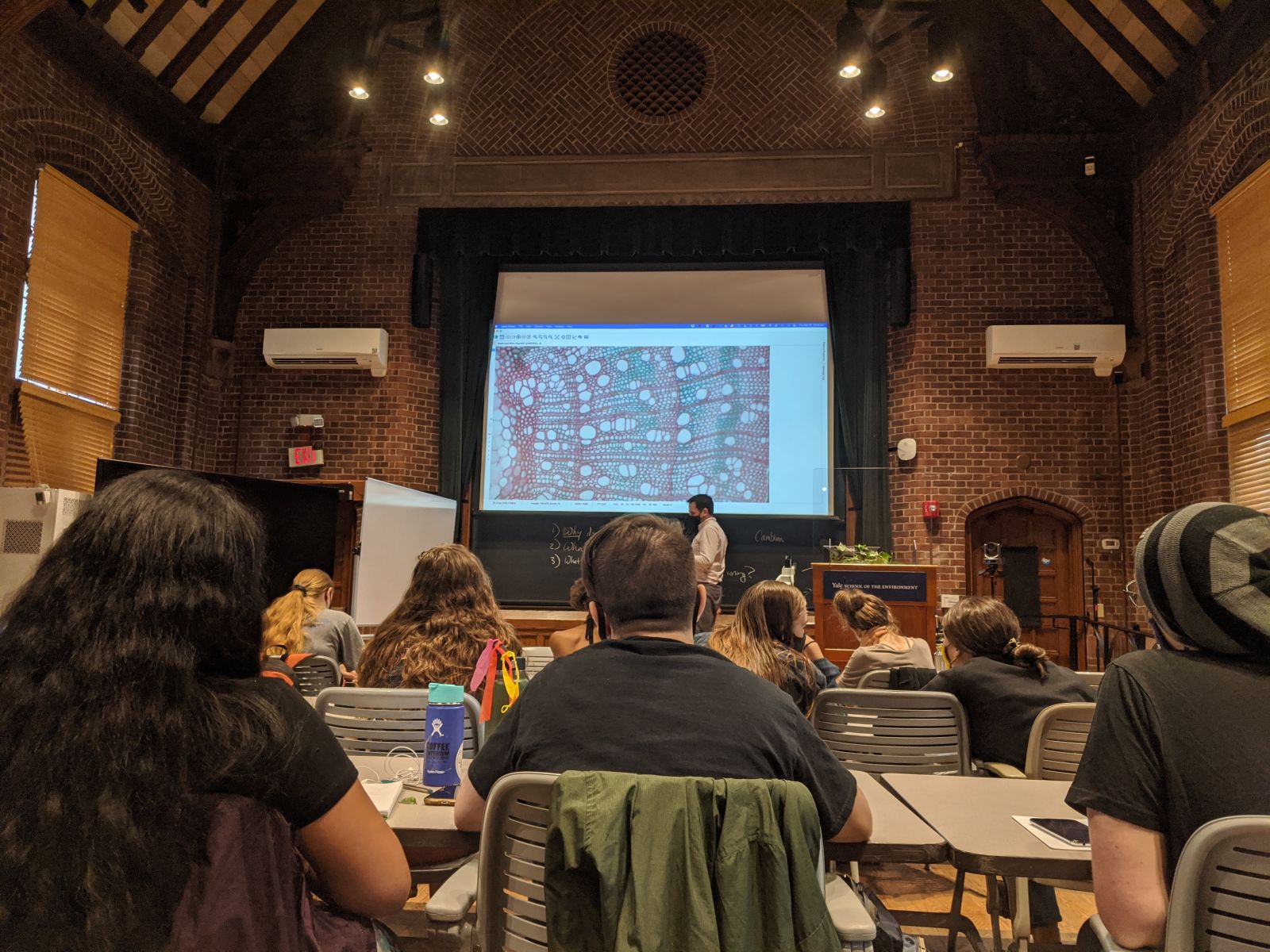

Professor Craig Brodersen lectures on plant ecophysiology as a guest speaker in dendrology in Bowers Auditorium. Photo by Isaac Merson ‘23 MEM.

Professor Craig Brodersen lectures on plant ecophysiology as a guest speaker in dendrology in Bowers Auditorium. Photo by Isaac Merson ‘23 MEM.

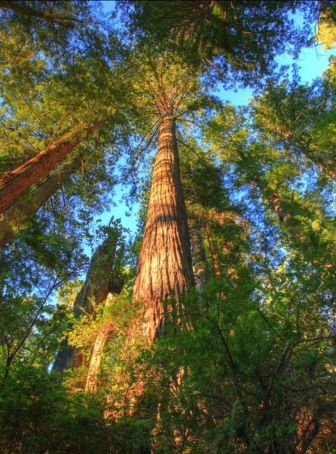

Duguid centered students in the temperate forests of the Northeast, covering topics from ecological models of succession, to plant interactions, tree architecture and growth, disturbance and forest structure, to regeneration, studying under the canopy, urban forests, to climate change, and old growth. Duguid brought in colleagues Professor Liza Comita to speak on forest fragmentation and climate, Professor Michelle Spicer on forest dynamics in the tropics, DEEP Forester Danica Doroski ‘17 MFS, doctoral candidate on urban forest dynamics, and doctoral candidate Eli Ward on mycorrhizal fungi’s interactions in the forest understory.

At her PITW in East Rock Park, Alison Robey observed mushrooms in the understory of a beech grove west of Whitney Peak (left, September 22, 2021; right, October 6). Photos by Alison Robey ‘26 Ecology & Evolutionary Biology doctoral student.

At her PITW in East Rock Park, Alison Robey observed mushrooms in the understory of a beech grove west of Whitney Peak (left, September 22, 2021; right, October 6). Photos by Alison Robey ‘26 Ecology & Evolutionary Biology doctoral student.

Coincidentally, Duguid and Ward shared the same instructor at the School, Ann Camp, as students in this course, which was then called Forest Stand Dynamics. Ward reflected that Duguid’s change of the name to Forest Dynamics makes it more accessible to anyone interested in the changes of plant life in this ecosystem.

Ward, who started her Master of Forest Science degree the year before Duguid arrived as a lecturer, remembers the hiring process for Duguid’s position and the vision of the Thomas G Siccama Lecturer to be focused on field learning. This is something that Ward believes Duguid has fully embodied with her own spin. On lecture days, it was not uncommon for Duguid to interrupt her lecture to take students outside for even twenty minutes to look at tree architecture. She also arranged to bring in potted trees to the classroom to demonstrate the growth patterns she lectured on.

Unlike Forest Dynamics, its sister course “Woody Plant Taxonomy and Dendrology,” which is also taught by Duguid, was not offered last year because of the pandemic. Therefore, most second-year MF and MFS students are learning the dendro basics in Professor Mark Ashton’s “Management Plans for Protected Areas” course. What is typically an all MF and MFS attended class, this fall’s had about two to three foresters out of 15 enrolled students. Again, word of mouth about this course and Duguid’s approach to teaching filled the course with students from YSE and Yale College, who are inspired by Duguid’s approachability, according to Duguid’s Teaching Fellow Walker Cammack ‘22 MF.

“Marlyse’s knowledge has been brilliant. Dendrology is so fun for her and it shows. It is infectious to be around her when she is talking about plants,” Walker describes Duguid’s knowledge and instruction of the taxonomy of plants.

In Dendrology, students of different backgrounds come to learn over 100 plants in the course of the fall semester. The first day of class started with half of a lecture in Marsh Hall and promptly migrated outdoors to learn the basics of taxonomy in Marsh Botanical Gardens. Every class day since occurred in the field in different parts of Connecticut: beach ecology at Hammonasset Beach State Park, East Rock Park, Pond Lily Reserve in West Haven, and a day of walking under New Haven’s urban canopy. The class even took a trip to the Berkshires to get a glimpse of the plant ecology of northern forests, including sightings of northern white cedar and chinkapin oak, which are not found in New Haven.

Duguid connected individual plants to their plant communities as well, identifying them within their habitats from wetlands to ridgetops. It therefore only made sense for weekly quizzes to be held in the field in a wide range of biological habitat factors, from wetland to sandy stands. Winding through the woods, students identified numerous plants by their common and Latin names, including genus, species, family, and order.

The only time students did not have their ears and eyes on Duguid, Cammack describes, is when students spotted an autumn olive shrub, a non-native species found in disturbed sights, to congregate around and enjoy its silvery, edible berries.

In these popular courses, Duguid creates both the conditions and compassion for students to show up curiously, learn rigorously, and be present in the woods and with one another. Tarino raves: “The students were remarkable, so engaged and asking brilliant questions.” There is no doubt about the popularity of these courses – pandemic or not – nor Duguid’s and her students’ shared desire to be immersed by the lessons in and of the woods.