By: Emily Sigman ‘21 MF/MA

This past winter, in between classes and field trips, Will Kessler ’26 MF spent a lot of time tapping maple trees. His goal, however, was not to make maple syrup — at least not yet. Instead, Kessler tapped trees in the city of New Haven, collected the sap in small sample bottles, and whisked the samples to a lab to be tested for heavy metals and PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances).

Kessler’s efforts this semester are part of a multi-year research project called “Safe Sugar for All.” The Safe Sugar project investigates whether maple trees growing in contaminated soils also have contamination in their sap and explores exposure mitigation strategies. The research is supported by a $500,000 grant that is housed at The Forest School at YSE. The principal investigator is Yale Forest’s Director of Forest & Agricultural Operations Joseph Orefice. Orefice teaches a class on maple each year and launched the school’s Maple Education & Extension Program. Emily Sigman ’21 MF/MA — a graduate of Orefice’s maple course — helped write the grant and design the study. She now leads the research as part of her doctoral studies at Dartmouth. The grant is a collaborative effort and includes partnerships with the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station and Dartmouth College, as well as with local groups across New Haven.

Prior to this research, Kessler had never tapped a maple tree. He eagerly jumped into the project, and it didn’t take long for him to learn the ropes. He worked alongside Sigman to assemble the sampling equipment and refine the collection protocol, providing key insights throughout the sap season that enabled the team to adapt as unexpected challenges arose. All winter, Kessler could be seen dashing through New Haven, power drill and sampling kit in tow, collecting sap from maple trees in city parks, backyards, and greenbelts. He also made frequent trips to the Yale-Myers Forest, which serves as a control site. Between February and April, the team collected nearly 400 samples from 100 different trees in 10 unique sites across Connecticut, Massachusetts, Vermont, and New Hampshire.

Will Kessler ’26 MF and Emily Sigman ’21 MF/MA stand with a freezer full of sap samples they collected from 100 trees growing in diverse landscapes across New England. Photo: Jasmine Jones

Although most maple syrup making (also called sugaring) takes place in rural areas with presumably low levels of contamination, people tap trees for personal use in all sorts of places — cities, roadsides, and even superfund sites. Yet many wonder, if you tap a tree that is growing in contaminated soil, is there also contamination in the sap? If so, what happens to that contamination as the sap is concentrated into syrup? And if there is contamination in the syrup, is there anything you can do to filter it out?

The team is working to answer these questions, and investigating a range of heavy metals, like lead, and different types of PFAS, commonly referred to as forever chemicals. Both heavy metals and PFAS are harmful for human health, but they come from different sources and may behave differently in ecosystems.

The team is also looking at different species of maple trees. In addition to sugar maple (Acer saccharum), they are also testing red maple (Acer rubrum) and Norway maple (Acer platanoides) — a tree that is considered invasive in New England.

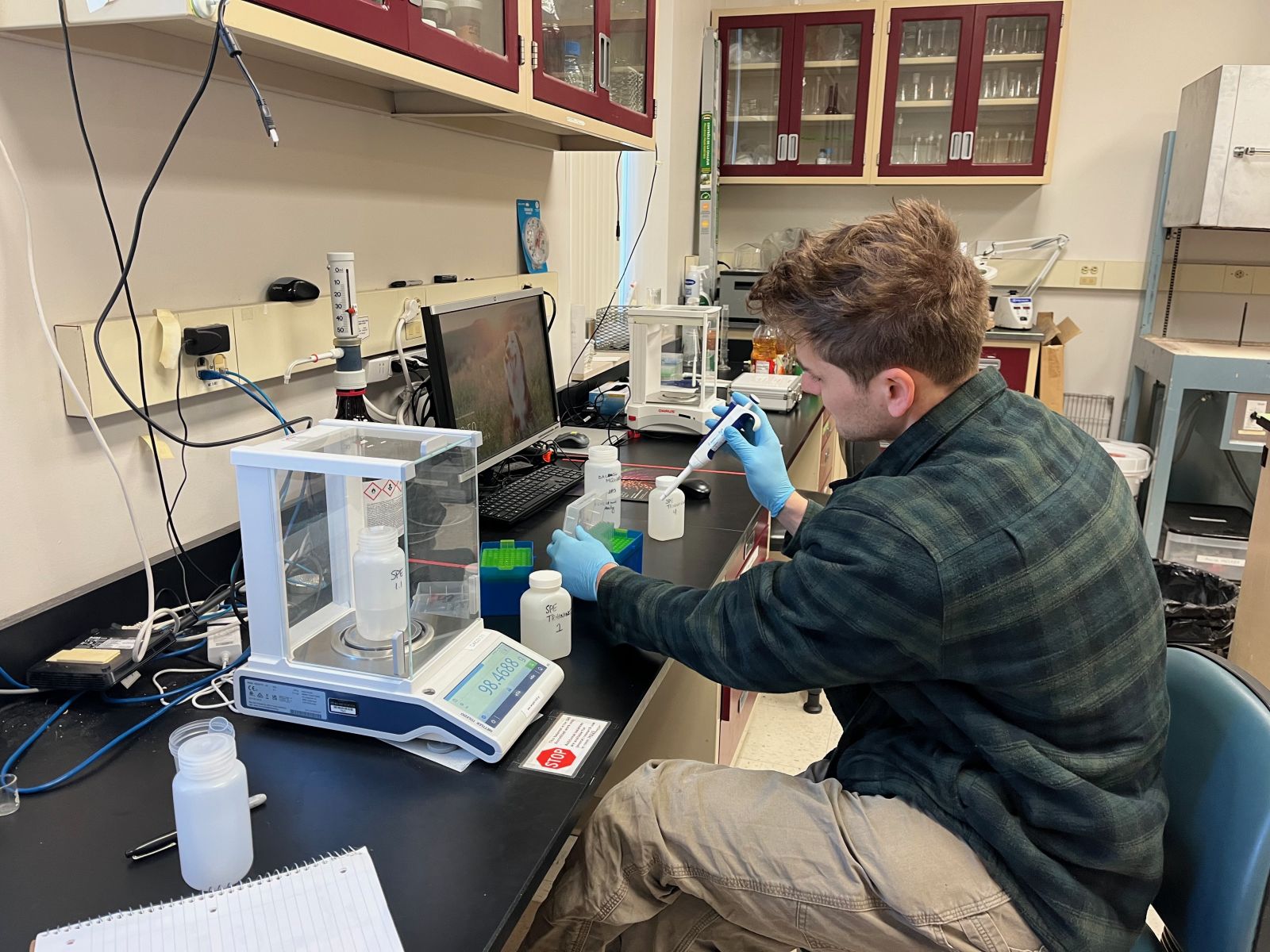

Kessler learns the process of Solid Phase Extraction, a key first step needed to test the sap samples for PFAS. Photo: Emily Sigman

By collecting soil and sap samples from a diversity of trees in a range of sites, the team hopes to be able to identify what risks, if any, soil-derived heavy metals and PFAS pose to sugarmakers in different places. They are especially interested in urban contexts. Urban sugaring could function as an effective way to help connect communities to their local environments and to each other. Indeed, interest in urban sugaring has grown in recent years, and many schools, community groups, and families already tap trees in urban places. Yet in the absence of peer-reviewed scientific studies that quantify contamination risks and elucidate contamination pathways, urban sugarmakers are forced to either ignore contamination concerns or halt their activities. The ultimate goal for the research team is to create a protocol that people who are living in potentially contaminated places can use to determine if, and how, they can safely make syrup from their trees.

Now that the sap season has drawn to a close, Kessler is learning a new set of skills, this time in the lab. With training from scientists at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, he is processing the sap samples so that they can be run through a specialized piece of equipment that detects PFAS. It’s an exacting and time-intensive process, but Kessler is up for the challenge. He’s excited, he says, to be having so many different kinds of experiences, and to see what, in the end, his samples reveal.