By Wyatt Klipa ’23 MEM

There is broad scientific consensus that in order to mitigate the worst impacts of climate change, humanity must work to not only substantially reduce or eliminate new greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions but also draw down the concentration of greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere. Leveraging forests, which store carbon in their biomass, to do so is receiving increasing attention from scientists, land managers, large corporations, and investors. However, misinformation and communication gaps run rampant in understanding just how forests can help draw down atmospheric carbon concentrations most effectively. Too often practitioners do not have the time, resources, or access to new scientific publications and research necessary to ensure that their work reflects the most up to date knowledge. Likewise, scientists who hope their research impacts management decisions have challenges communicating their findings beyond scientific journals. To address the gap between researchers and practitioners, The Forests Dialogue (TFD), Yale Center for Natural Carbon Capture (YCNCC), and Yale Applied Science Synthesis Program (YASSP) hosted a workshop to explore the question of the role of forests in a changing climate on February 1, 2024.

While hosting its steering committee in New Haven, Connecticut, TFD brought together researchers and practitioners in a workshop about managing forests in the face of climate change. Of particular interest was the question of whether forests will continue to serve as carbon sinks or become carbon sources on a regional level—that is, whether forests will have a net sequestration or emission impact on atmospheric carbon—as climate change progresses.

This topic drew interest from several collaborators: YCNCC supports research and workshops exploring the many novel approaches for atmospheric carbon removal, and YASSP, a research program of The Forest School at the Yale School of the Environment, synthesizes scientific research and consensus and delivers that information to decision makers. In addition to participants from all three organizations, this conversation also drew interest from multiple Yale forestry students and faculty members, who are interested in exploring the practice/research divide.

Researchers and practitioners collaborate to understand how on the ground decision making can reflect the most up-to-date science related to climate change impacts on forest carbon storage, February 1, 2024. Photo: The Forests Dialogue.

The session opened with two short scientific background talks from Sara Kuebbing, director of research at YASSP, and Paulo Brando, associate professor of ecosystem carbon capture at YSE, on the source/sink dynamics of temperate and tropical forests, respectively. Kuebbing shared that while the world’s forests serve as a net carbon sink globally—annually storing more carbon through photosynthesis and growth than is emitted via deforestation and other tree mortality—it is essential to understand source/sink dynamics with a regional and local context. For example, even while North American forests are an overall carbon sink, forests in the U.S. Rocky Mountains are currently a net carbon source, mostly because of drought and wildfire related mortality, which is exacerbated by climate change.

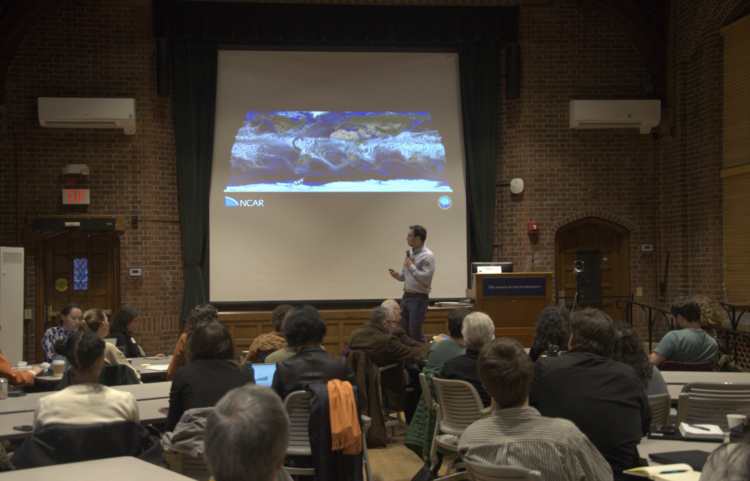

Brando noted that human management decisions also have a major impact on forest source/sink dynamics. The Amazon—the world’s largest tropical rainforest—is also a net carbon source. As the Amazon becomes fragmented and developed for agriculture, the newly formed edges are exposed to higher temperatures, reducing the amount of water held in the forest. The smaller the patches, the more these conditions can penetrate the forest interior. The dry edges have made the Amazon—historically a wet tropical rainforest—increasingly susceptible to fire mortality. Brando concluded that human management decisions have substantially impacted the hydrological cycle of the Amazon, helping to contribute to its shift to a net carbon source.

Paulo Brando, associate professor of ecosystem carbon capture, describes the water storage capacity of the Amazon, while noting the harms to that capacity due to fragmentation and climate change, February 1, 2024. Photo: The Forests Dialogue.

The group then heard from five different forestry practitioners from TFD’s steering committee. The practitioners shared their own stories of challenges they have faced while managing forests as the climate changes. They noted the need for more accessible scientific information and funding to help to address these challenges. Marthe Tollenaar, ESG director at SAIL Investments, focused on the challenges of directing money to the right types of forest management projects. Marcus Colchester, senior policy advisor at the Forest Peoples Programme, spoke of climatic shifts in Indigenous-managed lands in Guyana. Cécile Ndjebet, president of the African Women’s Network for Community Management of Forests, highlighted the loss of traditional forest foods due to climate change in her home nation of Cameroon and throughout Africa. Francisco Rodríguez, sustainable fiber and conservation manager at CPMC Celulosa in Chile, noted the opportunities that plantations may have to contribute to carbon storage. Finally, Kerry Cesareo, senior vice president for forests at the World Wildlife Fund, shared her hopes for a funding system beyond the current carbon offset market, to support forests for values beyond just carbon sequestration.

Cécile Ndjebet, TFD steering committee member, shares her perspective on the challenges climate change creates for local forest-dependent peoples throughout Africa while suggesting research needs, February 1, 2024. Photo: The Forests Dialogue.

After the group heard from both scientists and forestry professionals, they were split into small discussion groups comprised of a mixture of researchers and practitioners. Here they spent the bulk of the session, discussing the missing pieces of knowledge that each sector wished it had from the other. The groups also spent time discussing how best to bridge this gap and direct scientific research to where it can be most useful and relevant to practitioners. Groups shared their takeaways, which featured the following conclusions:

- Practitioners simply cannot access all new scientific knowledge, whether due to paywalls restricting access to journals or a lack of time to dedicate to reading through dense jargon and methods. The pathway of knowledge from the scientists producing it to the practitioners that need to hear it must be streamlined.

- For the sake of management and practice, not all research conclusions can be applied to all geographic scales and regions. Research agendas should focus on the regions and forests that are most in need of management direction. Regardless of these challenges, participants agreed that forests can be a valuable tool to help draw down atmospheric carbon while providing a suite of co-benefits, including clean water, biodiversity, and livelihoods through wood and non-timber products. Managers and scientists must now work together to identify how best to preserve these benefits in a changing future.

The Forests Dialogue’s complete summary report of the event, including full conclusions, can be accessed here.