By Sara Santiago ‘19 MF

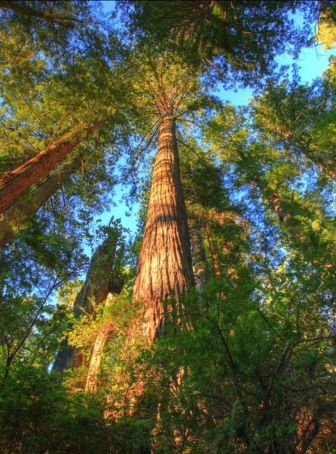

“You know it when you see it.” When grasping to describe mature and old-growth forests, this is a sentiment we often hear, evoking an image of mossy, sun flecked, big-treed forests. Yet, defining mature and old-growth forests is as important as ever. In April 2022, the Biden Administration released the “Executive Order on Strengthening the Nation’s Forests, Communities, and Local Economies,” which calls for science-based forest management and conservation of mature and old-growth forests. As public discourse buzzes over what should and should not be touched on public lands, select faculty from The Forest School respond to the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management’s public comment period.

Terry Baker ‘07 MF, CEO of the Society of American Foresters, asked faculty and staff of his alma mater to submit science-based guidance in response to the public comment request by the U.S. Forest Service and Department of Interior to define mature and old-growth forests on federal land (87 FR 42493). Mark Ashton, professor of silviculture and forest ecology, Mark Bradford, professor of soils and ecosystem ecology, Marlyse Duguid, lecturer in forest ecology, Gary Dunning, executive director of The Forest School, Sara Kuebbing, director of the Yale Applied Science Synthesis Program, and Joe Orefice, director of forest and agricultural operations at Yale Forests, penned a letter in reply.

Faculty Response

Select TFS faculty and staff write: “We welcome an inventory and, as a precursor, the need to define old-growth and mature forests. We assert that any definitions of ‘mature’ or ‘old-growth’ should be distinct from each other”—including “forest attributes that characterize distribution of tree age and size classes, level of structural complexity, and indicator plant and animal species.” Of further importance, they advise taking site specific variation into account, a testament to the School’s commitment to place-based science.

TFS faculty and staff make two leading statements on the definitions.

Concerning old-growth, “The USFS and Department of Interior should rely on existing, well-accepted characteristics of old-growth forests from the forestry and forest science academic community,” using the science of stand dynamics and accounting for variation across forests.

Further, “mature forests are poorly defined with a range of descriptive attributes that are vague. In academic circles the term is general and is used dependent upon biological, economic and social circumstance.”

They also draw in the human relationships —historical, enduring, and contemporary— with these forest types. The group states the agencies should consider that current day mature forests come from colonial land clearance and/or forest exploitation and human induced stressors (e.g., pests, pathogen, pollution, invasives, development, fragmentation, selective logging, climate change).

“Forests are human influenced, they have been for millennia and this is even more true today due to climate and other environmental changes. Hence, simplified and undiscerning forest ‘preservation’ policies that exclude the option of human management of forests in the US may lead to both local and global environmental injustice.”

As an institution dedicated to forest stewardship for over 120 years, the group reflects: “The USFS and Department of Interior should focus on protecting all forestlands, including old growth and mature forests.”

SAF Special Session on Definitions

At the annual convention in Baltimore, Maryland in September 2022, the Society of American Foresters held a “Special Policy Engagement Session: Let’s Talk Old-growth and Mature Tree Management.”

Dr. Jamie Barbour of the U.S. Forest Service introduced the session, sharing that the agencies have received over 100,000 comments and they will work to make the distinct definitions over the next 2-3 years. While the Forest Service last defined mature and old-growth forests in 1989, there have been many definitions for many different forest types, Barbour explained. There are also misinterpretations around the current endeavor, such as the difference between optimizing and maximizing the amount of carbon sequestration found in these important forests as well as environmentalists calling for a hands-off approach.

Terry Baker invited Joe Orefice to provide comments on old-growth and mature forest management on behalf of the TFS group. Orefice delivered the guidance and stressed the difficulty with defining these forests based on disturbance as there has been substantial disturbances on the American landscape.

Orefice also made a plea: forests and people have always been together. People have always impacted forests. Don’t take people out of forests.

Joe Orefice directs the Forest Crew Apprenticeship Program at Yale Forests, teaching sustainable harvesting and conservation strategies to master’s students. Photo by Ian Christmann.

Logging in the Public Eye

Arguably more than ever, forests occupy the minds of the public—from debates around the sentience of trees, to the urgency around sequestering carbon, to fears over logging within certain forests.

In a YSE Q&A, Mark Bradford and Joe Orefice address public calls to abandon all logging.

Orefice explains tenants of Western forest science: “As trees grow, they need more space and their competition for light resources increases. By cutting one tree, we can give another tree more room to grow and increase its health.”

Bradford continues: “The argument for removing forest management entirely from our nation’s forests ignores the strong science around how you manage for healthy, resilient forests. For example, our New England forests have been managed by people for thousands of years and more recent actions have left many of our forests in a degraded state. If you ban forest management now, you will reinforce a cycle of decreasing forest health as less desirable tree species become ever-more dominant in even-aged, mature forests that have a low ability to recover from the growing intensity of pest, pathogen, and climate disturbances.”

“Admittedly, these lands might still look like a forest in that you have mature trees with closed canopies. But they lack vigorously growing, younger individuals of desirable species, such as red oak, which are of high value for timber, wildlife, and carbon storage. The false narrative in New England that ‘nature will fix itself’ ignores the current state of many of our forests and the critical role that sound forest management plays in restoring and sustaining forest lands and the livelihoods of those that depend on them.”

In offering science-based comments, TFS strives to promote sound forest management in New England and across the U.S. No doubt, varying voices and debates will continue to arise as the agencies work toward collective definitions to guide the stewardship and management of the nation’s forests.