Sara Santiago ’19 M.F.

Marlene Miller Pratt is a mother and educator, born and raised in New Haven to a Black family with roots in North Carolina. She had mostly raised her own family in the South, though her son, Gary Keysean Miller, moved back to New Haven in 1997. In 1998, Pratt received news her son was shot and killed. With immense grief, Pratt returned to New Haven to find the person that murdered her son.

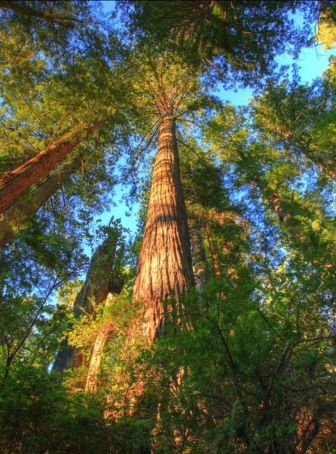

In processing her grief, Pratt found herself seeking peace and remembrance in Yale’s Marsh Botanical Gardens. The warm, humid greenhouses bursting with plants in various shades of green and the outdoor garden with its trees, shrubs, and flowers from around the world brought solace. There she would “look at the life – even though it was plant life,’’ she says.

At what she refers to at her “serenity spot” at the Gardens, Pratt questioned how she could continue to advocate for and honor her son after his death. Finding the gardens to be a place of healing, she wondered what might it be like to create a healing garden dedicated to the memory of those lost to gun violence? A place, she thought, where other New Haven parents who have lost their children could find refuge.

Marsh Botanical Gardens’ staff introduced Pratt to Colleen Murphy-Dunning, director of Urban Resources Initiative (URI), a program associated with The Forest School at the Yale School of the Environment.

URI practices community-based forestry (CBF), a type of natural resource or forestry management that is directed by an empowered and self-defined community. Its approach is to meet community needs in a collaborative and sustainable effort.

More than 20 years after her son’s death, Pratt asked for support to create a healing garden to honor all victims of gun violence in New Haven and in doing so, found a collaborative and empathetic partner with URI. Pratt also gained companionship in her healing. Through a support group in New Haven, Pratt found community with other moms – Pam, Winnie, and Celeste – who also lost their children to gun violence. In this group, Pratt says she had a “sigh of relief, I found my peers.”

These four moms became a nucleus of core leaders who created the New Haven Botanical Garden of Healing Dedicated to Victims of Gun Violence. Together, they shared their grief and plans for the garden. In group meetings, they envisioned an environment for healing through community-based forestry, and they dug into the physical work of designing and planting.

“URI plants trees for people all of the time for various reasons. URI often plants for a significant event – the birth of a child, to honor someone who has died,” says Murphy-Dunning. As a CBF initiative led by New Haven Moms, she describes a particular goal: “For this community, it’s stemming gun violence and healing.”

Nature promotes healing because we as humans have an innate connection with nature as we are ourselves part of it, she says.

The New Haven Botanical Garden of Healing is believed to be the first permanent space in the country that commemorates the daily loss of life in a community.

For the garden project, URI hired Svigals + Partners architectural design team, who had worked with the Sandy Hook community to design a new elementary school after the 2012 shooting deaths of school children and faculty, to create the landscape design for the New Haven botanical garden.

In spring 2019, the core group of moms broke ground in West Rock. Since then, they have planted along the West River and carried out the installations and landscaping throughout the garden.

At the opening of the garden is a large engraved memorial stone that states: “We do this in loving memory of you” followed by the names of the moms who established it.

The garden opens with a large engraved memorial stone: “We do this in loving memory of you” followed by the names of the mom organizers. Visitors can follow a walkway made of bricks that are engraved with more than 600 names of victims of gun violence in New Haven and the years they died. This pathway ends at the tree of life and a memory wall, which evokes the emotion of tragedy not unlike that at the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C. The botanical garden also houses a sculpture dedicated to the lost lives and a tree of life for a place of reflection.

The project has received support from many parts of the community. Former Governor Dannel Malloy and former New Haven Mayor Toni Harp worked with URI and Pratt on securing public land and funds. Jackie Fouse ’19 MEM provided a significant gift for the initiative. Common Ground High School students and incoming Yale College freshman researched and identified 275 next of kin of victims of New Haven gun violence in an effort to inform them about the site. The moms then sent letters to the families describing the memorialization of their loved ones in the botanical garden and invited them to preview it before its public opening.

It was a process that was both emotional labor and emotional healing, Murphy-Dunning says. When the family members visited, the core moms took them on a tour and then gave them time on their own at the memorial wall to reflect. About 200 family members toured the garden in the first visitation weekend alone.

The healing work at the garden continues. Since the new year, seven people have been murdered via gun violence in New Haven: Alfreda Youmans, 50, Jeffery Cornelius Dotson, 42, Jorge A. Osorio-Caballero, 32, Marquis C. Winfrey, 31, Joseph “Joey” Vincent Mattei, 29, Kevin Jiang, 26, and Angel Luís Rodríguez, who was 21. The names of all seven victims are on their way to being engraved on bricks, which will be added to the garden.

The Yale School of the Environment joins with all the families mourning the victims of the violence, Murphy-Dunning says. Jiang, a Yale School of the Environment (YSE) student ’21 MESc, was killed on Feb. 6.

“We are devastated by the loss of Kevin as we are also of the untimely and violent deaths of all the others in New Haven,’’ she says.

As a continued collaboration, Pratt has plans for future phases of the project to help curb gun violence. Drawing upon her experience as an educator, Pratt is creating a curriculum for fifth grader students on bullying and for eighth graders on guns, drugs, and self-esteem and to use the garden as an outdoor classroom. Pratt is also designing a mentorship program. The brick walkway of names is meant to motivate adults to understand the gravity of violence and to take action, and Pratt would like that to include mentoring youth.

While the New Haven Botanical Garden of Healing Dedicated to Victims of Gun Violence has not necessarily been framed as a racial equity or justice initiative, the core moms hope for social change in their hometown of New Haven. Ultimately, the moms would like to break the numbness the public has when hearing about another shooting and to create a physical space to witness and reflect – a space to talk about the future.

For updates on this unfolding creation, visit the project’s page on the URI website.